What Do We Know About the Link Between Affluence and Political Responsiveness?

One of the most heated discussions in Political Science in recent years has revolved around whether the rich are more politically influential than the average voters. Gilens and Page (2014), which found that economic elites and organised business groups dominate policy making in the United States, is probably the study that most people are familiar with. Following its publication, the study received a lot of publicity; enough for the authors to be invited on the Daily Show with Jon Stewart to discuss their findings, and the paper even made it to the top ten of the most highly cited studies from the 2010s (see full list here). Other highly cited and publicised studies that point to a similar conclusion as Gilens and Page (2014) include Bartels (2008), Gilens (2005), and Gilens (2012). Yet while these highly influential studies all suggest that the rich exert an outsize influence of public policies, a more nuanced picture emerges when considering the literature as a whole.

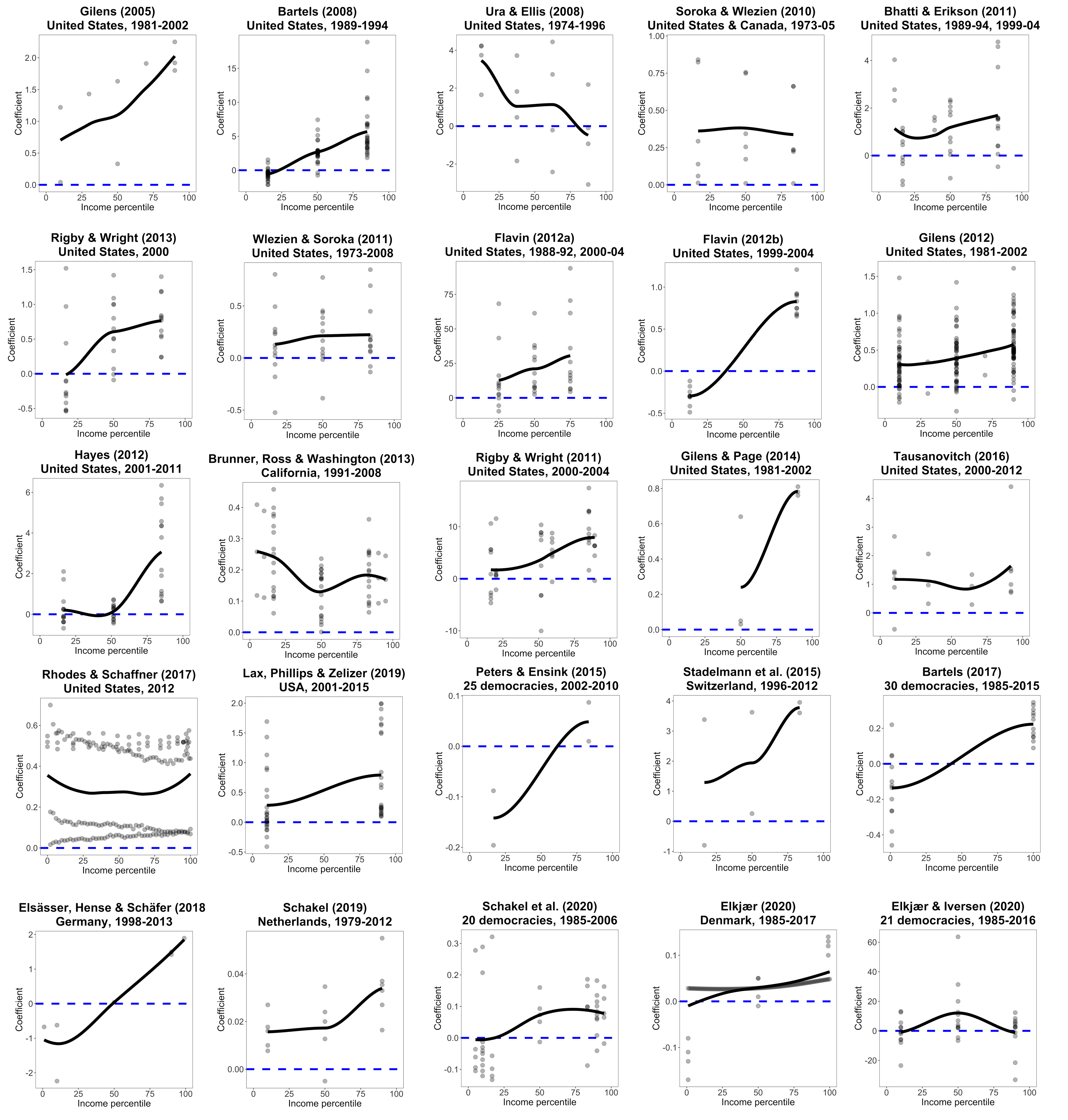

In a new working paper (with Michael Baggesen Klitgaard), I conduct a systematic review of the literature that studies the link between affluence and political responsiveness (the most recent version of the paper can be found here). Figure 1 below graphically illustrates the results of the 25 studies that examine how affluence (measured in terms of income) affects political responsiveness. The x-axes are the position of an income group in the income distribution, whereas the y-axes are estimates of political responsiveness (specifically, the size of coefficients from regressions that regress some measure of policy output on related public preferences). Higher values on the x-axes correspond to higher income and higher values on the y-axes correspond to stronger political responsiveness. For instance, Gilens (2005) finds a strong positive association between income and political responsiveness, suggesting that the preferences of higher income groups are better represented in public policies compared to groups with lower incomes.

While a majority of the 25 studies finds a positive income gradient in political responsiveness, there is considerable heterogeneity in results across studies. Wlezien and Soroka (2011), among others, find no association between affluence and political responsiveness; the results of Ura and Ellis (2008) and Brunner, Ross, and Washington (2013) suggest that on average the poor are better represented compared to the rich; and using comparative data Elkjær and Iversen (2020) find that middle-class preferences are better represented in redistributive government policies than those of either the poor or the rich. How can we explain this divergence in results?

Figure 1: 25 Studies of Differential Political Responsiveness

In the systematic review, we examine how the results differ across (1) regions of the world (essentially, the U.S. vs. Europe), (2) levels of aggregation of policies and preferences (does a study use specific or aggregate measures of policies and preferences), (3) policy issues (economic vs. non-economic), (4) partisanship of one’s representative or government, and (5) different model specifications. The review shows, surprisingly, that studies of European countries, on average, find the same degree of unequal political responsiveness as studies of the United States. Results do not depend on the level of aggregation of policies and preferences, but the degree of unequal political responsiveness can partly be explained by issue type and partisanship. On average, the middle class and the rich are more equally represented on economic issues compared to non-economic issues, and Republicans in the United States respond more strongly to the preferences of the rich than to those of the poor compared to Democrats. Yet the strongest predictor of the severity of unequal political responsiveness is the model specification: statistical models that include more than one set of preferences in the model specification produce more extreme findings. In fact, a clear majority of the published findings which suggest that the rich completely dominate the lower income classes are produced by these multivariate statistical models, which include the preferences of several income groups simultaneously.

Some scholars interpret the model dependency to reflect disparities in substantive political responsiveness. Gilens and Page (2014), for instance, argue that the multivariate model captures the relative influence of different groups, whereas the bivariate models, which include the preferences of income groups in separate models, merely capture alignment between policies and preferences. Others, most notably Bashir (2015), argue that the model dependency is likely to reflect statistical issues caused by high correlations of the preferences of different income groups. For instance, the preferences of the middle class and those of the rich correlate by .94 in the raw data from Gilens and Page (2014). How exactly to make sense of the differences in results across models remains hotly debated and solving this issue should be a top priority for scholars in the field.

Potential Explanations of Differential Political Responsiveness

While the systematic review points to the importance of issue type, partisanship, and the model specification for understanding differences in results across studies, it does not explain why results are so similar across the United States and Europe. Figure 1 shows strikingly similar patterns of unequal representation in the United States, across Western democracies, in Switzerland, Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark. One should think that the significant differences in the political-economic contexts of these countries would cause different patterns of unequal representation, but that is not reflected in the results. So how can we make sense of the similarities in distributions?

In my recent paper with Torben Iversen, we argue that the similarities in results may simply reflect that individuals with higher income, on average, are better informed about current political and economic issues and therefore adjust their preferences more closely to the political-economic context. For instance, if individuals with higher income are better informed about the need for counter-cyclical spending, then any government that pursues standard New Keynesian policies would appear to respond more strongly to the preferences of high-income citizens, even if the spending level perfectly matches the interests of another class. The key distinction here is thus whether one studies short-term changes in policy settings or long-run levels of policies. In the paper, we show that whereas changes in redistributive policy reflect the preferences of the affluent, the long-run levels reflect the interests of the middle class. This may suggest that the striking similarity in results across the widely different political-economic contexts reflects differences in information across groups, rather than disparities in substantive political representation, since the studies examine short-term policy trends. Studying the Danish case (Elkjær 2020), I find further support for this argument. Thus, although short-term trends in policies correspond more closely to the preferences of better-informed groups - across income groups, that is the affluent - the middle class may remain politically pivotal.

Types of Affluence

An open question remains how different types of affluence are related to political responsiveness. In other words, is there any systematic variation depending on whether we look at income or wealth? The systematic review discussed above includes only studies that examine the link between income and political responsiveness. This is not so much because of an inherent interest in income as it is due to a lack of studies that examine other types of affluence. To the best of my knowledge, there are no published studies that have examined how different types of asset ownership are related to political representation. Again, this is not because of a lack of interest, but rather because surveys rarely include questions about both asset ownership and policy preferences, making it impossible to measure preferences for different types of asset owners consistently across contexts or over time. Thus, it very much remains an open question whether disparities in substantive political responsiveness exist across citizens with varying wealth. We hope to be able to shed light on this question in future research projects.