Perceptions Of Wealth And Why They Matter

In early December 2015, Tamil Nadu, a South Indian state, faced the worst floods in over a hundred years. An estimated 188 people died, and over 100,000 people were displaced due to the heaviest rainfall in over a century and poor civil infrastructure. Many observers raised questions concerning the slowness of the government's relief efforts and its effects on the severity of the disaster. One such criticism came from Kamal Haasan, a famous Indian film actor who resides in Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu. In an interview with an Indian news website, the actor said, “It’s a nightmare for the poor and the middle class. The rich should feel guilty. I am not so rich and yet I feel guilty when I look outside my window and see how people in my city are suffering.” Complaining about the government's lack of willingness to end social inequality, he added: “I love my people truly. All this drama of rich and poor is a farce, though. The politicians don't give a damn about social equality as long as they remain in power.”[1]

Perhaps it is unsurprising that citizens complained about government services and relief efforts, especially if they believed that if the government had taken timely and appropriate action, the storm would have done less damage. What is surprising here is that Haasan, one of India's most prominent and richest actors, remarked that he is not “so rich”. Furthermore, he urges ‘the rich’ to feel guilty about the unequal consequences of the flood and calls on them to take action. However, with a net worth over one hundred million dollars and a recent agreement to be paid over 2 million dollars for hosting the Tamil-language version of reality show Big Brother, Haasan is indeed among India's most affluent.

There are many more examples of affluent people exclaiming “Me? But I am not rich!” from all over the world. In 2015, New Jersey governor Chris Christie – whose household income was about $700,000 in the previous year – replied to a reporter asking if he considered himself a wealthy man: “I don't consider myself a wealthy man. Listen, wealth is defined in a whole bunch of different ways and in the end my wife and I have worked really hard, we have done well over the course of our lives, but, you know, we have four children to raise and a lot of things to do. So no, I don't consider ourselves [to be wealthy], and I don't think most people think of me that way.”[2] Yet an annual income of $700,000 puts the Christie family in the top one percent in the American household income distribution.

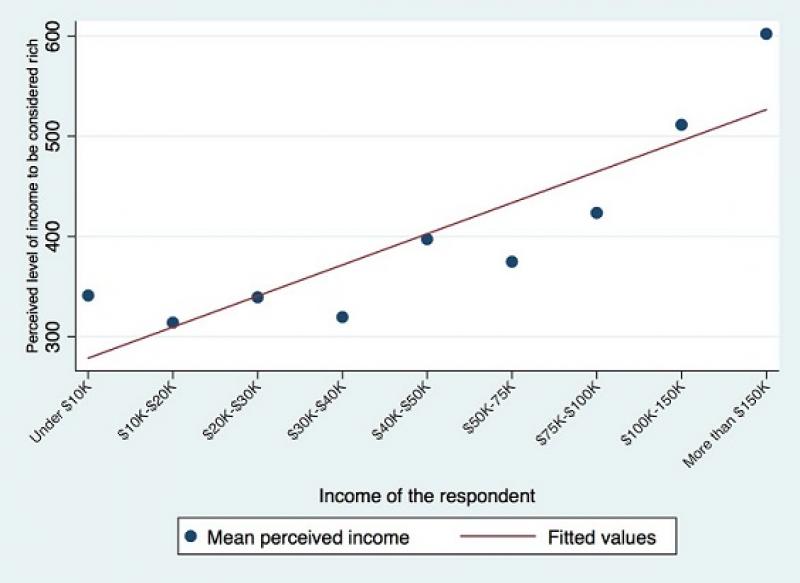

The stories of the Indian actor and the New Jersey governor are not isolated anecdotes. Few affluent people consider themselves ‘rich’. For example, a Pew survey of 2011 confirms that only 1% of Americans identify themselves as ‘upper-income’, although about 21% would actually be defined as such. Data also shows that many Americans define ‘rich’ as anyone who earns more than they do. Evidence from the Pew Research Center’s survey about income inequality presents interesting evidence about the direction and magnitude of this regularity in the United States. Looking at the graph above, every income group, on average, thinks that a household has to make more than $300,000 a year to be considered rich. But as the income of the respondent rises, so does their prediction of how much the rich make a year. On average, most of people think ‘the rich’ make significantly more than what themselves earn.

Theoretically, the curious cases of Kamal Haasan, Chris Christie, and the other misperceivers should not strike political scientists as either surprising or implausible. Many studies have carefully documented how citizens are poorly informed about political facts. In particular, a plethora of recent studies have demonstrated that people misperceive both the level of economic inequality and their own position. Furthermore, individuals also make significant mistakes about how much certain groups make a year.

On the face of it, these numbers introduce a simple yet a compelling regularity: for most citizens ‘being rich’, it seems, is a fuzzy concept that is hard to define. As a result, everyone (high and low income alike) think that the rich consist of others – perhaps the Bill Gates or the Mark Zuckerbergs of the world, or the owners of the nicest house on the block. Or, perhaps, it is an unknown person who lives on the Upper East Side in Manhattan, shops from Saks Fifth Avenue, drinks champagne for brunch, and takes exotic vacations in French Polynesia. Who do you have to be to be rich?

Konda Research and Consultancy has asked a representative sample of Turkish respondents precisely this question: In your opinion, what is the main fault line between the rich, the middle class and the poor? The options included the area that an individual resides in, education level, fashion style, car, and earnings. Almost 52% of the respondents agreed that the residential area was most crucial, separating the rich from the poor, whereas only 27% said it was the type of the car owned by an individual that mattered the most. Surprisingly, 28% of the respondents agreed that fashion style was an essential identifier of social class. Finally, 65% of the respondents thought earnings were an important aspect of defining social classes – which means that the rest of the respondents (35% of the whole sample) did not believe earnings mattered for being described as ‘rich’.

These results show that people have various ways of deciding who is rich. The findings have, of course, important implications for research on wealth inequality. How do we assess views about the rich if people form their opinion on the affluent based on stereotypes rather than facts? How do people with different definitions of wealth evaluate wealth inequality? As the WEALTHPOL team, we are now trying to answer these questions.