The rise and fall of inheritance taxation in advanced democracies: towards the death of the “death tax”?

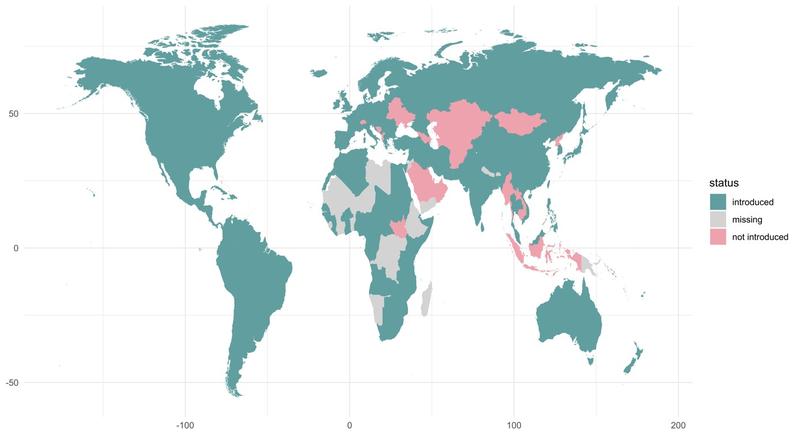

The taxation of inheritances has made a come-back in public debates in recent years following a renewed interest for the roots and consequences of, and solutions to increasing wealth inequalities in advanced democracies. Inheritance taxes go by a variety of names – “death duty” or “death tax”, “stamp tax”, “estate tax”, “succession tax” and many more – and are an object of great controversies over the normative basis for taxing inherited wealth (Boadway et al. 2010). Inheritance taxes are among the oldest forms of taxation, dating back to the Roman Empire, thus preceding by far modern forms of taxation like the personal income tax. Inheritance taxes broadly refer to the tax levied on the person who inherits the estate of a deceased individual.[1] They constitute an attractive fiscal tool to the extent that they do not require much administrative capacity compared to other direct taxes (as they are levied only once in a lifetime), and are a priori both an efficient revenue-raising levy and one that has the potential to significantly reduce inter-generational wealth inequalities (Piketty and Saez 2013). Inheritance taxes have been introduced in a majority of countries worldwide, as shown in Figure 1 below. Nevertheless, the past decades have seen a global movement away from inheritance taxes, first and foremost in advanced industrial democracies: Canada abolished it in 1971, Australia in 1979, New Zealand in 1993, Sweden in 2004, and Australia in 2008 (Scheve and Stasavage 2012; OECD 2018). Because tax repeals are very rare – tax introductions are in general sticky – this trend is of particular interest.

Figure 1. Inheritance Taxes in the World

Source: Tax Introduction Dataset (Seelkopf et al., 2019) and own calculations.

Note: The map displays countries in which an inheritance tax has been introduced at some point in time, whether the introduction was sovereign or not. It does not take into account cases when the tax was later on repealed (on this, see above).

Meanwhile, revenues from inheritance and gift taxes have always been very low, and declining over time, dropping from 1.1% of total tax revenues in 1965 to only 0.4% on average in OECD countries by 2018 (OECD 2018). This figure reflects the fact that the associated tax bases are considerably narrowed by numerous exemptions and deductions, and undermined by avoidance opportunities. The wealthy can and do engage in estate management over the course of their lifetime, by transferring assets to their heirs tax-free before their death, or by placing their inheritance in wealth trusts that benefit from a much more favourable tax regime (Scheve and Stasavage, 2012). Former Chancellor of the Exchequer Roy Jenkins famously described the inheritance tax in the United Kingdom as “a voluntary levy paid by those who distrust their heirs more than they dislike the Inland Revenue”. On the other hand, as Mirrlees et al. (2011) note, bequests are most often not purely accidental but at least partly planned by donors – even if the latter are not among the “super rich”. It follows that inheritance taxes will systematically (and negatively ) affect donors’ savings and consumption decisions during their lifetime, giving credence to those who oppose the taxation of inherited wealth on the grounds of economic efficiency.

Economists and political scientists have thus engaged in efforts to provide empirical evidence on the effect of inheritance taxes on wealth inequality and its perception, and on preferences for taxation in advanced industrial democracies. Bastani and Waldenström (2019) explore how attitudes towards inheritance taxation are influenced about information about the role of inherited wealth in society using a randomized survey experiment in Sweden. They find that informing individuals about the importance of inherited wealth at the aggregate level and its relation to inequality of opportunity significantly increases support for inheritance taxation. This suggests that one explanation behind the relatively marginal role of inheritance taxation in developed economies could be the low salience of inherited wealth in society. In Sweden still, Elinder et al. (2018) estimate the causal impact of inheritances on wealth inequality, using the official wealth register of Statistics Sweden. Their results indicate that inheritances reduce wealth inequality measured by the Gini coefficient or by top wealth shares, but increase its absolute dispersion. This suggests that individuals’ behavioural responses are not large enough to compensate for the main equalizing effect of inheritance. Similarly, in a 2006 study about the United States, Conway and Rork also find that behavioural responses are not going in the expected direction: testing the hypothesis that the elderly move away to avoid “death taxes” using inter-state migration data, they find no evidence that estate, inheritance and gift policies impact this type of elderly migration. Taken together, these results show that research on the effects of inheritance taxes has only scratched the surface so far.

An issue that arises if one wishes to go beyond country-specific studies is the lack of comparable data on inheritance taxes. The ground-breaking 2012 study by Scheve and Stasavage has provided reliable time-series data on top marginal inheritance tax rates in 18 countries, exploiting a myriad of legal and historical sources for each country, and allowing for cross-country comparisons. A limitation nevertheless is that the top rate only tells part of the story – especially since, as Jenkins pointed out, there may ultimately be very few people wo end up paying this rate on their bequest. Just like for income therefore, we need to look at the whole schedule, which becomes highly complex due to differences in design across countries – including but not limited to the definition of the taxpayer unit and the base, the rate structure, and special treatment of some assets (OECD 2018). One challenge is to establish, for each country and year, what a “typical inheritance” is, from which one can derive the rate applied to bequests of this size, smaller or larger by some factor, and draw meaningful comparisons. As part of a new WEALTHPOL project, we are gathering data on inheritance tax rates applying to small, medium and large inheritances, defined as multiples of annual income, in over 20 countries from 1945 to the present day. This data, which will be in the public domain, should prove an invaluable resource for scholars of wealth inequality, policymakers, and the general public. Stay tuned!

References

Bastani, S. and D. Waldenström (2019). Salience of Inherited Wealth and the Support for Inheritance

Taxation. Technical Report 7482, CESifo Group Munich.

Boadway, R., E. Chamberlain, and C. Emmerson (2010). Taxation of Wealth and Wealth Transfers. In Dimensions of Tax Design: the Mirrlees Review, pp. 100. Oxford University Press.

Conway, K. S. and J. C. Rork (2006). State "Death" Taxes and Elderly Migration. The Chicken or the Egg?

National Tax Journal 59 (1), 97{128}.

Elinder, M., O. Erixson, and D. Waldenstrom (2018). Inheritance and wealth inequality: Evidence from

population registers. Journal of Public Economics 165, 17{30.

Mirrlees, J., S. Adam, T. Besley, R. Blundell, S. Bond, R. Chote, M. Gammie, P. Johnson, G. Myles, and

J. M. Poterba (2011). Tax by design. Technical report, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Piketty, T. and E. Saez (2013). A Theory of Optimal Inheritance Taxation. Econometrica 81 (5), 1851–1886.

Scheve, K., & Stasavage, D. (2016). Taxing the Rich: A History of Fiscal Fairness in the United States and Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Seelkopf, L. et al. 2019. ‘The Rise of Modern Taxation: A New Comprehensive Dataset of Tax Introductions Worldwide’. The Review of International Organizations

OECD (2018). The Role and Design of Net Wealth Taxes in the OECD. Technical report, OECD.

[1] The general trend has been that of a move away from estate taxes – levied on the deceased donor – towards modern inheritance and gift taxes – levied on the beneficiaries. Nonetheless, some countries, including the United States, still have a donor-based system.